-

United States -

United Kingdom -

India -

France -

Deutschland -

Italia -

日本 -

대한민국 -

中国 -

台灣

-

-

產品系列

查看所有產品Ansys致力於為當今的學生打下成功的基礎,通過向學生提供免費的模擬工程軟體。

-

ANSYS BLOG

July 14, 2022

Engineering a ‘Soft Collision’ Between Humans and Humanoid Robots

Halodi Robotics was founded in 2015 by CEO Bernt Øivind Børnich and COO/CFO Stein Erik Maurice to innovate humanoid robot helpers that they couldn’t believe were not already in existence. What was the roadblock? After a lot of deep thought about what they wanted from such a robot, they used simulation and their considerable ingenuity to create Eve, “the world’s first robot to operate with human strength, in near silence, to safely work among (and interact with) people.” After talking with with Børnich, we wanted to share his fascinating insights into the intersection of the human and robotic worlds with you.

Ansys Advantage: What inspired you and your colleagues to start Halodi Robotics?

Bernt Øivind Børnich: The goal from the start has been to get robots out of factories, among people. It's been a lifelong dream for me and everyone else in the company. We're all waiting for robot helpers around us, and it didn't seem to be happening by itself. So, we really started by sitting down and looking at why it is not happening. What are the major barriers to enter this market? What's actually lacking to make it happen? Because it's one of those rare things where everyone's asking for it, everyone wants it, but it doesn't exist.

AA: And what did you conclude from these discussions?

Børnich: We figured out that there are some fundamental principles about how we build robots that don't align with how you would get robots to be useful in human environments. In brief, we need to make robots that are safe, capable, and affordable. There have been a lot of products through the years that have had two of these, but none that have had all three.

AA: Can you give us some examples?

Børnich: Yes. There are some human-like products that can wave and talk, things like that. But in my opinion, they are not real robots because a robot is an automator — it automates work. And if you can't automate physical labor, you're not really a robot. They are relatively safe, relatively affordable, but they are not capable.

And then you have the capable robots, which I would say are the industrial robots. They're capable, they're starting to get affordable, but they're not safe. Whenever they're picking up something, there's a pattern — they move quickly and precisely, and then they almost stop, and then they move again. And this is because, when moving, the energy in the system is so high that if the robot touches anything, either the robot breaks or whatever they're touching breaks. They're inherently not safe. They can be made safe in a controlled factory environment, around trained personnel, but there are still safety barriers to enter the market for general interactions with humans.

AA: What are you doing at Halodi to make robots that are safe to work with humans?

Børnich: We are getting rid of all this energy so that the robot can just collide with the world without breaking the world or itself. That's what we humans do. When you go down the hallway in your office space, you're not afraid of bumping into your colleague. It might be awkward, but it's not dangerous.

Our design for our first robot, Eve, is very much inspired by biology. And it just comes down to that we humans are masters of minimizing impacts and we're inherently “over damped.” So, whenever we do anything, we have so little energy in our motions that collisions are very low energy. We don't care about the impacts. When I pick up something, I do that by colliding with it. Even when I pick up my coffee cup, I collide with the cup.

Eve can interact with things, including humans, in a compliant, soft, natural manner. It’s able to exert a lot of force, but it’s moving with minimal energy. And this is really where our system sets itself apart. When you interact with our robot, you'll feel it; it's just like interfacing with a human, everything is just soft and compliant and everything gives way, but it can still exert a lot of force because those two things aren't necessarily related. So, Eve can be very strong, but still very low energy. And that's something that's been missing in robotics. It’s really what opens up the market to us because it enables us to be safe.

AA: How did you engineer gears, motors, and connecting cables between the joints of the robot?

Børnich: We use very similar systems to human muscle fiber — synthetic fiber threads that are shared between a lot of our actuators to move the robot. And we do that together with very-low-speed motors that have very high torque, and very low weight. Eve has about three times more power to weight than anything you can buy commercially off the shelf in that size, so it's really a game changer.

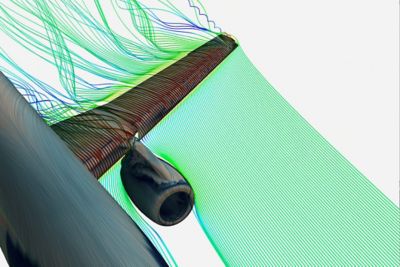

At the core of this problem is, how do you get force or torque density so that you can have a lot of power with very little speed and still very little weight? Because then of all your other problems become not simple, but a lot simpler. And it's a very hard problem to begin with. So, we've been spending a lot of time doing large optimization models, utilizing Ansys simulations among others to figure out the best way to design electric motors.

AA: How did you decide to use Ansys software?

Børnich: Originally, Ansys software was prohibitively expensive for us as a startup. We would not have been able to use it without the Ansys Startup Program. That's been hugely beneficial to us because the other simulation tools aren't the same quality, and we've evaluated all of them. So, the Startup Program has been very empowering, and we're very grateful for it.

AA: Which Ansys simulation products do you use the most?

Børnich: If you look at hours spent, it's Ansys Mechanical, because everyone in the engineering team working on the product is doing so much simulation on the component side. But the big work we're doing is on the motor side, which I'm super hyped about. My key contribution early in the company was doing all the motor designs. I still do most of it — that's where I keep my hands dirty. For that we use a mix of some in-house tools and Ansys Motor-CAD.

Motor-CAD has a very efficient way of solving simulations for motors, so that you can actually iterate on large-parameter models and do optimization. We do a lot of analysis of frequency-dependent losses. Which of our frequency-dependent losses actually matter at the speed that we’re running the motors, and how can we use that to either improve performance or simplify the system and then verify that it works in the real world? We’re utilizing Ansys solutions among others to figure out what's the best way to design electric motors.

And now we're spending a lot of time on “design for manufacturing” for motors, especially for a new generation where we're setting up proper assembly lines for high-volume production.

AA: So you’re planning on mass-producing these robots?

Børnich: Exactly. And having really good simulation models there is invaluable, because you always have your production engineers asking, "Can we do this? This will make manufacturing a lot simpler.” And we need to decide how this proposed procedure would actually affect performance. Sometimes we run a design for manufacturing simulation and discover that it would completely wreck performance. And other times we learn that it wouldn’t affect the performance much, so we say, “Let’s do that.”

Being able to answer such questions within a couple of hours using simulation is super important. For the company, now, it's a really big thing to go deep on the manufacturing side and make sure that what we have is not only very high performance, but that it satisfies the original three criteria: safety, capability, and affordability. If you do a really good job on automating your manufacturing, you can also make your product at a disruptively low cost.

AA: What are your target markets for these robots?

Børnich: We want to get into security, retail (such as warehouse work), logistics, and healthcare, for starters. We're seeing a lot of traction right now in physical security. We just closed the largest deal ever for humanoid robotics, with 140 robots scheduled to ship late this year to a security firm.

Because our robots are powerful, in addition to being able to patrol around and observe and report, our robot can open doors, including heavy doors. In secure facilities, you have heavy doors with heavy door pumps. You need to exert a lot of force to be able to open them.

We are also able to map humans really well to the robot. So, we have a very powerful avatar mode where we map all of the kinematics of the human to the kinematics of the robot. The robot actually has exactly the same joints and ranges of motion on joints as a human, including the leg, except that it has one leg with wheels instead of two legs.

This enables us to do remote labor very efficiently. Our robot can do fine manipulation, like closing a window, removing a bag that someone put in a door, etc. So, in this application, we have a fleet of robots covering a building with a central human operator overseeing the fleet. When a robot finds a bag blocking a door that should be closed, it asks for help. The operator takes control of robot, removes the bag, and the robot continues automatically. And this enables us to cover all the edge cases. Every time the robot doesn't know how to handle a situation and a human steps in and does it through avatar mode, the robot learns how to do it.

This also delivers better service for the customer because there's a lot of things robots are really good at and there are things that humans are really good at, and we want to use them both for whatever they do best. If a robot is doing after-hours patrolling and there's not supposed to be anyone there, and he opens a door and sees a person in the room, he alerts the operator. The operator talks to the person through the robot, including mapping his body language through the robot, to resolve the situation.

AA: You also mentioned healthcare applications. How do you envision that working?

Børnich: As the human population ages, assistive robots can help people to live better, more independent lives without leaving their homes through use of technology. They can also help with care in hospitals, like moving patients around in wheelchairs or helping them to get dressed. Simple things like getting out of bed in the morning when you want to get up, not when the nurse has time. Or bringing you food when you're actually hungry, or helping you dress when you want to go out. Helping people — that's really what gets me up in the morning. That's where we want to take Halodi Robotics in the long term.