-

United States -

United Kingdom -

India -

France -

Deutschland -

Italia -

日本 -

대한민국 -

中国 -

台灣

-

Ansys는 학생들에게 시뮬레이션 엔지니어링 소프트웨어를 무료로 제공함으로써 오늘날의 학생들의 성장을 지속적으로 지원하고 있습니다.

-

Ansys는 학생들에게 시뮬레이션 엔지니어링 소프트웨어를 무료로 제공함으로써 오늘날의 학생들의 성장을 지속적으로 지원하고 있습니다.

-

Ansys는 학생들에게 시뮬레이션 엔지니어링 소프트웨어를 무료로 제공함으로써 오늘날의 학생들의 성장을 지속적으로 지원하고 있습니다.

ANSYS ADVANTAGE MAGAZINE

May 2021

Simulating to Win the Indy Autonomous Challenge

By Ansys Advantage Staff

On June 30, 2021, autonomous Indy Cars will race around the Indianapolis Motor Speedway at speeds of up to 180 mph, making history as the first high-speed driverless race. As the exclusive simulation sponsor for the Indy Autonomous Challenge (IAC), Ansys has supplied 485 students on 40 teams from universities around the world with Ansys SCADE software to generate the embedded control code that will guide the autonomous vehicles on the course. The teams also have access to Ansys VRXPERIENCE, which they can use as a virtual reality driving simulator to test their embedded software in a safe virtual space before putting real race cars on the track. The winner will receive a $1 million prize and bragging rights as the first autonomous racing champion in the world.

To help these teams get ready for the IAC, Ansys has held a series of “hackathons.” These hackathons are designed to show the engineers how to use simulation to design autonomous control code and test it in scenarios of gradually increasing difficulty using virtual cars racing on a virtual model of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

“The IAC is a test bed for developing autonomous technology and the brain power that goes into it,” says Tarun Tejpal, Ansys’ industry marketing director for transportation. “An autonomous race car is basically a supercomputer on wheels. The teams have to optimize that supercomputer and the only way you can do that is with Ansys simulation technology.” He notes that the hardware and software have been coming together over the last decade to bring autonomous driving closer to reality. “Now it’s just a matter of human ingenuity,” he says. “By putting these student teams in a competitive situation, they will exponentially innovate the autonomous technology that will eventually be used in commercial automobiles.”

Teams have been making great progress to date as evidenced by their performance at the hackathons. To give you an idea about what the journey has been like for one team, we talked to Gianluca Papa and Filippo Parravicini, both Ph.D. candidates from the poliMOVE team from Politecnico di Milano, Italy, about their experiences with the IAC. They have 30 members, including doctorate and master’s degree candidates, most of whom have automation and control engineering backgrounds, together with a few students from the mathematics, aerospace, mechanical engineering and computer science departments. Oh, and don’t forget their advisor, Prof. Sergio Matteo Savaresi, who was “super enthusiastic” about the project from the start, according to Papa and Parravicini.

The Hackathons

Hackathon #1

At the first hackathon held last year, Ansys simulation experts introduced the teams to Ansys SCADE and Ansys VRXPERIENCE. The experts taught them how to use the software to begin developing embedded code to guide their virtual autonomous cars around a high-fidelity model of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

One autonomous challenge the teams had to face was avoiding an evasive maneuver, then rushing across the finish line.

“We have a pretty strong background in vehicle dynamics control, but this was our first experience with autonomous racing. So, we were starting basically from scratch,” says Parravicini. “We looked at learning the Ansys simulation environment as a challenge, but an interesting one. We didn’t back off and we tried to get the best from it. SCADE and VRXPERIENCE are very powerful, very interesting tools.”

Hackathon #2

Held in September 2020, at the second hackathon the teams were expected to demonstrate their virtual race car driving on the Indy track, powered by SCADE embedded software. In the first heat, each team occupied the race track alone and tried to post the fastest lap; in the second heat, two other race cars were placed on the track in front of the team’s car and they had to try to pass without crashing while still posting a fast time.

To achieve the fastest lap requires a team to find the best line around the racecourse. In the event, some teams seemed to wander slowly back and forth between the inner boundary of the track and the outer wall, staying within the boundaries all the time but sacrificing speed to do so. A couple cars made unexpected excursions into the infield of the track or crashed into the wall, disqualifying them from this hackathon with a DNF (Did Not Finish) result.

In the first heat, involving 21 cars, the poliMOVE car hugged the inside line of the racecourse as close as possible throughout the whole race, leading to a first place finish in a time of 1:14:75, just beating out the Crimson Autonomous Racing (University of Alabama) and the Black & Gold (Purdue University and West Point) racing teams who tied for second place at 1:14:85.

“What we’re looking for is the minimum lap time trajectory,” Papa says, explaining the team’s strategy. “It doesn’t matter for us if it’s the shortest path. If there’s a longer one but with a higher speed, we take that path. In the VRXPERIENCE driving simulator, we try to iterate our work and to re-look to find the optimal trajectory. Our goal is to do our best in every lap, at every time, in every situation.”

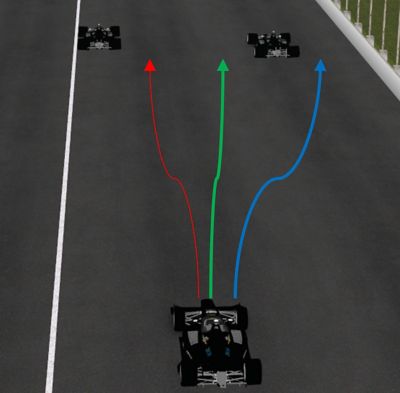

In the second heat, involving 18 cars, most teams opted to pass the two cars in front of them on the outside, with a couple passing between the two cars and a couple taking a low line under both of the cars. One team crashed into a lead car when trying to pass. This heat was conducted on the straightaway between the second and third turns of the Motorway, a much shorter run that the first heat.

Team poliMOVE passed between the two cars and registered a time of 13:850, which put them in a tie for first place with eight other teams in the second heat. Their combined performance in both heats — 50 points for first place in each — gave them a perfect score of 100 on the day, making them the winners of Hackathon #2.

Hackathon #3

By the time of this hackathon on January 21, poliMOVE was looking like the team to beat, with several teams close behind them. This time the teams would be competing head-to-head, two at a time on the same course, so the task was more complex: finding the best line while avoiding an encounter with the other car.

In preparation for this hackathon, the poliMOVE team increased the number of simulations they ran. In the process, besides enjoying the ease of using SCADE’s graphical interface to develop embedded code in a blockwise manner, poliMOVE engineers found another feature they liked best.

“You have the ability to include entire pieces of C code inside your main scheme in SCADE,” says Parravicini. “This is one of the things that we are exploiting the most to give us more control over the autonomous performance of our race car.”

SCADE generates C code from a block diagram, including any custom blocks poliMOVE engineers might create. “When you’re done with your development process with SCADE, you have an executable file and you run it. You make it talk to VRXPEREINCE, you see the results, you analyze your data and then you go back to SCADE.” Papa says.

All these iterations paid off again in the hackathon. This time, each of the 18 teams that competed was paired with another for a set of two head-to-head heats, which required them to complete five laps without incident while staying within the boundaries of the track. poliMOVE drew TUM Autonomous Motorsports from the Technical University of Munich as their opponent.

In the first heat, poliMOVE set the record for the fastest lap of the entire competition, with a time of 46:384 on laps 2, 3 and 4 to beat TUM. In the second heat, TUM made an aggressive, track-crossing maneuver in front of poliMOVE at the start of lap one, which caused the poliMOVE car to slow down to avoid a collision. Though they again beat TUM, the loss of time in the first lap caused poliMOVE to finish second in Hackathon #3 to Crimson Autonomous Racing of the University of Alabama.

“If you look at Hackathon #3, you can see that in general we are quite aggressive, and we are always looking for the optimal line,” says Papa. “We are not afraid of potential interaction and potential overtakes. I don’t know if this is the winning solution — only time will tell.”

“But if something dangerous is happening, this second heat showed that we slowed down to avoid that situation, and we always try to do that in the optimal way,” Parravicini notes. “You always have a compromise between performance and safety, but in the end, you have to try to win, right?”

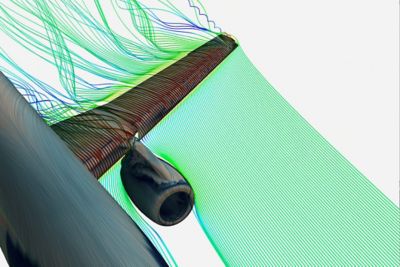

Renderings representing different camera views around an Indy Autonomous Challenge race car.

Autonomous Challenges Ahead

Though they are certainly happy with their performance so far in the IAC virtual events, Papa and Parravicini know that the biggest challenges are up ahead for all the teams. The teams will be given the keys to a real race car in June, and they will have to transfer their software from the virtual world to the real one. The poliMOVE team will send a small group over to the United States to start testing the software on an actual race car. They will have a lot of work to do.

“The current simulation environment using virtual cars on a virtual track is valuable, but it is clearly skipping the perception part of the autonomous racing challenge,” says Parravicini. “In the virtual races, you have very nice sensors that very nicely tell you exactly where the opponents are, their speed and their orientation. When you get to the real car, of course, there’s a whole different situation. You have to understand how all the sensors are working. You have to understand and take into account all the possible non-idealities of the sensors’ operation and then try to fuse all the information and get the best from each sensor to obtain the best possible estimation of what’s happening around you.”

Given all that, will they be able to win the IAC? “That,” says Parravicini, “is the million-dollar question.”

시작하기

엔지니어링 과제에 직면하고 있다면우리 팀이 도와드리겠습니다. 풍부한 경험과 혁신에 대한 헌신을 가지고 있는 우리에게 연락해 주십시오. 협력을 통해 엔지니어링 문제를 성장과 성공의 기회로 바꾸십시오. 지금 문의하기