-

United States -

United Kingdom -

India -

France -

Deutschland -

Italia -

日本 -

대한민국 -

中国 -

台灣

-

-

产品组合

查看所有产品Ansys致力于通过向学生提供免费的仿真工程软件来助力他们获得成功。

-

ANSYS ADVANTAGE MAGAZINE

May 2022

NASCAR’s 2018 announcement that it would develop a new type of race car, called Next Gen, which would be used as a platform by all race teams in the NASCAR Cup Series, predictably raised some eyebrows and caused an outcry among race teams and fans of the sport. With all the things that could potentially go wrong in designing a new race car, why take the risk? And why throw away decades of innovations created by engineers, mechanics, and drivers to optimize their car’s performance?

But NASCAR officials had their reasons. Fan attendance at racetracks was down, and the stock cars that raced under the banner of the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR) now bore little resemblance to the actual stock cars rolling off assembly lines and into dealerships around the world. In fact, though they were touted as the latest in automotive engineering, the race cars were using highly modified versions of automotive technologies of the 1960s and ’70s, tweaked for ever greater performance by engineers over the years.

John Probst, senior vice president of Racing Innovation at NASCAR, sums up the challenge as one of “relevance.”

“We need a racing platform that will make us more relevant to our original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) and our fans,” Probst says. “One thing that was plaguing us was that the suspension technology on the car was from the 1960s. We hadn’t really migrated with the pace of the automotive industry very well. With respect to that, our race car bodies were more like sedans than racing coupes. And it’s no secret that the internal combustion engine has a lot of pressure on it from electric hybrid and fully electric powertrains. So, we had to become more relevant to our fans, our automotive OEMs, our stock car heritage, and the environmental realities.”

On the business side of racing, the cost of owning a race car team was reaching outrageous levels — in the eight figures range — just to start with a modest team of a couple race cars, a driver, and some engineers and mechanics. This was keeping new owners from entering the sport at a time when NASCAR was interested in expanding. The plan for Next Gen was for all teams to order standard parts from the same vendors to build their cars so costs could be reduced and monitored, perhaps opening the doors to a new crop of team owners.

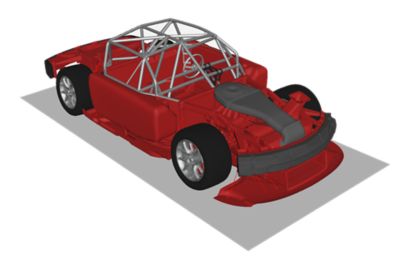

The Next Gen project started with a clean sheet of paper and input from NASCAR owners, teams, and drivers, all of whom weighed in on the front end and identified what they wanted the new car to be able to do. How did they want it to race, and how much did they want it to cost? All their responses were shared with the designers to turn that sheet of paper into a working race car.

With plans to launch the Next Gen race cars at the start of the 2020 season, NASCAR had a lot of engineering to do in a short time. Ansys LS-DYNA, a standard NASCAR simulation solution, was always going to play some role in simulating crash tests to reduce the high costs (approximately $500,000 per test) of running physical crash tests. Then 2020 came and the world stood still. Even the crash test facilities that NASCAR had traditionally used closed their doors because of the COVID-19 pandemic. LS-DYNA was needed more than ever.

Safety First

The NASCAR Next Gen racecar features a new sequential five-speed shifter.

“Safety is our number-one priority at NASCAR,” Probst says. “When we feel like there’s a safety issue, we fix the issue and then go find the funds to pay for it. I won’t say money is no object, but we attack safety issues very seriously with whatever resources we need to get to the correct result.”

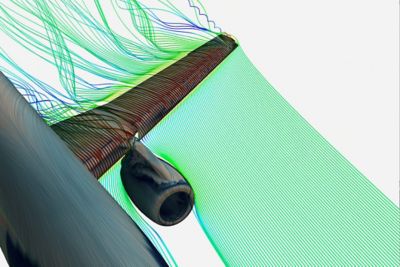

Ensuring the safety of the Next Gen race car fell to John Patalak, Managing Director, Safety Engineering at NASCAR. Patalak became a convert to LS-DYNA simulation while working on a project with a major automobile manufacturer to improve the crash safety of NASCAR drivers. LS-DYNA simulates the response of materials to short periods of severe loading.

The first time I was really very impressed with LS-DYNA simulation work was in 2011,” Patalak says. The project included a simulated human body model to test the restraint system in the automobile, including the seats, the shoulder supports, and the rib supports around the torso of the driver. “Frankly, I was blown away by the level of detail that you could get using LS-DYNA and the human body model — data that crash test dummies simply just don’t provide.”

While working for NASCAR, Patalak attended graduate school at the Wake Forest University Center for Injury Biomechanics, where LS-DYNA was the standard simulation software for studies of high impact on the human body. He soon became a champion of LS-DYNA at NASCAR.

His expertise and confidence in LS-DYNA were crucial to making progress on the Next Gen car while crash test labs were closed during the pandemic. For the first time, the bulk of the crash testing would be handled by simulation.

After more than 5,000 Ansys LS-DYNA crash test simulations, it took only two physical crash tests to verify and validate that the design was safe.

Putting LS-DYNA to the Test

“From the first prototype car level, we committed to meshing out and building a full LS-DYNA car model,” Patalak says. “That immediately allowed us to start assessing the car in all the different crash modes that our race cars encounter: frontals, roof crashes, lateral side impacts, rear impacts, and oblique impacts. We then focused our efforts on particular areas where we wanted to change performance or where we saw opportunities to make things better.”

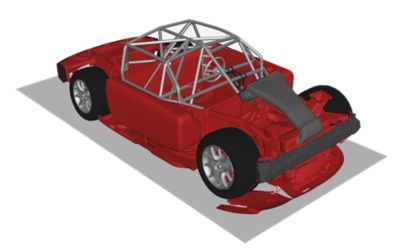

Because designs change rapidly in the prototype stage, LS-DYNA was particularly helpful in enabling engineers to make a change and immediately assess it in many different crash modes. For example, the team was trying to get more deformation out of the front clip (the front section of a car’s frame, which is designed to crush when it hits another car or a wall) at different points as the project progressed, but they also wanted to ensure that the changes were not unknowingly introducing negative consequences for other crash modes, such as a T-bone.

“With LS-DYNA, we’re able to run all crash scenarios and assess the effects of a design change,” Patalak says. “Was it holistically a positive change or a negative change, or what were we missing? These are things that you just don’t have the resources to do using physical testing. Being able to quantify these effects with simulations really improved the level of confidence we had in the overall design of this new vehicle.”

During the design process, Elemance, an engineering company dedicated to human-centered design using the virtual human body model developed by the Global Human Body Models Consortium (GHBMC), performed tests for NASCAR using Ansys LS-OPT, a design optimization and probabilistic analysis package. LS-OPT uses an inverse process of first specifying the performance criteria and then computing the best design according to a formulation.

Thousands of bumper simulations were run using LS-OPT, and soon NASCAR became so satisfied with the results that they committed to having these parts built without any physical crash test data.

“These were not prototype parts but pre-production parts,“ Patalak says. “When we finally had a chance to physically crash test them later on, the validation and correlation between the physical test and the simulation model was uncanny.”

Getting Next Gen to the Starting Line

Over the course of the Next Gen design project, NASCAR and Elemance ran more than 5,000 Ansys simulations to ensure the new car would be safe in any crash scenario. They started with a third-party cloud solution early in the process, then switched to Ansys Cloud, run on Microsoft Azure in mid-2021 to gain the benefits of having a single source for their simulation software needs. They identified the HC-series Virtual Machine, which features 44 Intel Xeon Platinum 8168 processor cores, as the best hardware configuration both in terms of performance and cost.

One of the biggest advantages of using a single software supplier for simulations, according to Patalak, is that you have only one company to call to solve any problems that arise. There is no other company to blame.

“The really nice thing about running jobs on Ansys Cloud was that it was all in-house,” he says. “I had very few issues, but just getting anything up and running on a new platform, it takes some time to learn the settings and which clusters to send jobs to, the memory settings, etc. It was nice because it was never someone else’s fault. The turnaround time and the support from the Ansys Customer Excellence (ACE) team was great — it was a one-stop shop for troubleshooting and answers.”

After more than 5,000 crash test simulations, it took only two physical crash tests to verify and validate that the design was safe and the results of the LS-DYNA simulations were accurate.

“From an engineering standpoint, our confidence in Ansys simulation is high. The results of a physical crash test are not a surprise to us anymore,” Patalak says.

Gentlemen, Start Your Engines!

But would the Next Gen car be ready for the first demonstration race at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, a stadium converted into a one-quarter-mile short-track racing venue, on Feb. 6, 2022? Despite the skeptics and the ups and downs of the design process, it was — much to Probst’s relief.

“If we didn’t have Ansys LS-DYNA, I’m not sure the Next Gen car would have been ready for the 2022 season because of everything being so disrupted by the pandemic,” Probst says.

The Next Gen race cars made their public debut in May 2021 and were first demonstrated in an early February race.

In the end, the coliseum race was successful, and was a proper lead-in to the most anticipated event in the NASCAR season: the Daytona 500, which kicks off every NASCAR Cup Series. Held Feb. 20, it resulted in 23 crash reports from the 40 cars in the race, with no significant injuries to the drivers. The Auto Club Speedway 400, held in Fontana, California, on Feb. 27, was similarly successful.

“We were happy leaving Daytona with the knowledge that what we expected to see from our modeling work was playing out on the racetrack,” Patalak says. “At Fontana, we had more and different types of crashes and, again, good outcomes. The results are matching very closely with our expectations that were shaped through LS-DYNA, which is showing itself to be true on the racetrack in real crashes.”

Probst agrees.

“From a higher level, I would say that we feel like we’re off to a phenomenal start with respect to all the targets around the Next Gen project,” he says. “There’s still a lot of work to do. We’re pleased but never satisfied on our end. But when you look at some of our fan metrics, when you ask somebody something as simple as ‘Was that a good race?,’ those numbers are actually off the charts right now, which we think bodes really well for this car.”

现在就开始行动吧!

如果您面临工程方面的挑战,我们的团队将随时为您提供帮助。我们拥有丰富的经验并秉持创新承诺,期待与您联系。让我们携手合作,将您的工程挑战转化为价值增长和成功的机遇。欢迎立即联系我们进行交流。