-

United States -

United Kingdom -

India -

France -

Deutschland -

Italia -

日本 -

대한민국 -

中国 -

台灣

-

-

产品组合

查看所有产品Ansys致力于通过向学生提供免费的仿真工程软件来助力他们获得成功。

-

ANSYS BLOG

March 6, 2022

Capturing Cancer with SmartCatch

Almost everyone knows at least one person who currently has or has had cancer. With more than 1.9 million new cases of cancer every year in the United States alone, it’s hard not to know someone affected by this terrible disease.

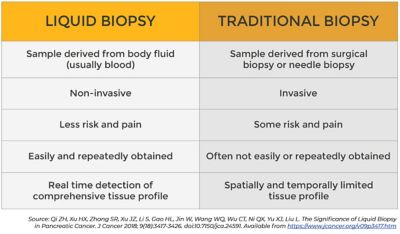

Biopsies, removal of tissue to examine under a microscope, are the most common way to diagnose cancer. The type of biopsy a patient receives is based on where the tumor is located. While some biopsy techniques are non-invasive, others require surgery that can be expensive, uncomfortable for the patient, and require longer healing times. Another downside of traditional biopsies is that diagnosis based on the analysis of a single‐tumor biopsy only reflects a single point in time of the whole disease.

But there is an alternative: liquid biopsies.

Catching Circulating Tumor Cells with Liquid Biopsies

A liquid biopsy is a minimally invasive procedure that tests blood for circulating tumor cells (CTCs) that travel in every patient's bloodstream. CTCs are cancer cells that escape from a tumor and migrate through the body. Some of these tumor cells travel through the bloodstream until they potentially develop a secondary tumor or metastasis.

Because they are pieces of the original tumor, they carry information about the presence, nature, and aggressiveness of the solid tumor. CTCs provide crucial information like number, genetics, molecular pathways, and mechanisms of immune evasion. Their detection, counting, and analysis could help doctors refine cancer diagnosis and prognosis, adapt therapies at the individual level, and closely monitor both the evolution of the disease over time and the effectiveness of the treatments.

The challenge is that these cells are incredibly rare, with only one CTC per billion normal blood cells. They are also difficult to capture while maintaining their physiological integrity. Because they are difficult to detect, they are not used in clinical routines as biomarkers, missing a great opportunity for early detection of cancer.

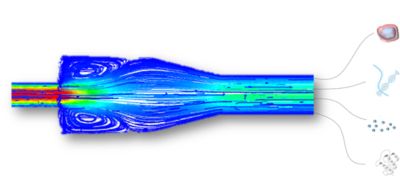

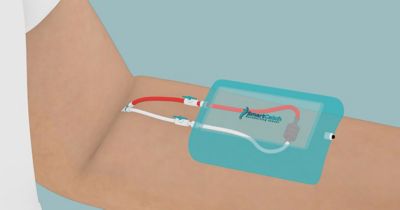

But CTCs are relatively larger and less deformable than other blood cellular components. Using a micro mesh capture device developed with cutting-edge technologies and advanced computational simulations, SmartCatch is working toward liquid biopsies that enable a one-step physical and selective isolation of CTC from blood in physiological conditions.

This technology is still relatively new but SmartCatch is paving the way to make liquid biopsies of CTCs accessible to everyone.

Figure 1. Liquid biopsy vs. traditional biopsy

How SmartCatch Casts its Net

Based in Toulouse, France, SmartCatch was founded in 2016 as a spin-off of the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS). Jointly founded by an academic team specialized in micro and nanotechnologies from the Laboratory of Architecture and Analysis of Systems (LAAS-CNRS) and urology surgeons of the University Institute of Cancer (IUCT) and Montauban Uropole, SmartCatch creates liquid biopsy technologies to empower clinicians, researchers, and the industry in the fight against cancer.

“Our goal is to develop highly normative technologies that are affordable, easy to use, patient friendly, and do not require particular training so that everybody can use them,” says Aline Cerf, chief executive officer and co-founder of SmartCatch. “We just want to detect cancer better, earlier.”

Cerf explains that the idea occurred to the founders in 2012.

“We came up with this crazy idea of developing 3D fishnets at the micro scale to isolate these tumor cells that everybody was really looking to be able to capture,” she says. “Because if you're removing the most aggressive elements, the ones that are responsible for metastasis, then you can prevent metastasis altogether.”

At the time, it was the advent of 3D technologies, not the type of 3D printing we think of today. They could make designs with great resolution, but it would take a long time. That’s when they decided to use Ansys simulation solutions.

Filtering Cells with Ansys Fluent

Thanks to the Ansys Startup Program, the SmartCatch team gained access to Ansys Fluent to simulate many filter design ideas.

“It would take us a full day to fabricate just one design and it was a lot of work as we had thousands of ideas per minute! So, we were wasting a lot of time. Ansys was the only tool that gave us the possibility to resolve the hydrodynamic phenomena at the scale and the meshing we needed to study them,” explains Cerf.

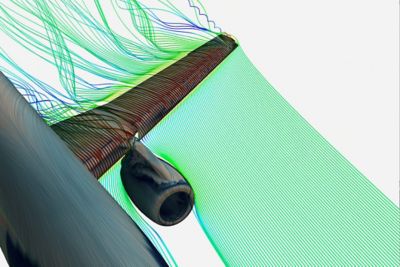

Figure 2: Numerical simulations in the development of medical devices designed to isolate cancer biomarkers from circulating blood

Blood, which is a complex viscous and multiphase fluid, is a very complicated liquid to simulate. All the cells within blood have different stiffnesses and deformability sizes. Part of the problem when SmartCatch began the project was that the technology just hadn’t caught up to where they were yet.

“For several years we had known the technical bottlenecks liquid biopsies were facing,” says Cerf. “We have reached a point where biology at the cellular level and the outstanding progress of micro/nanotechnologies now meet and we can finally solve these bottlenecks.”

Fluent has enabled SmartCatch to isolate CTCs directly from fresh, whole blood with no pre-processing steps to provide unaltered, high-quality capture material. “Because we're working in physiological conditions, we need to preserve laminar flows and prevent turbulences,” says Cerf.

Overcoming Regulatory Hurdles with Simulation

Every country has its own governing body that regulates pharmaceuticals and medical devices. In the United States, it’s the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In France, it’s the National Agency for the Safety of Medicines and Health Products (ANSM). Every agency has different rules, but the same basic principle applies to all of them: You must prove safety and efficacy before going to market.

“There are a lot of regulatory aspects to consider. For us, most importantly, we need to demonstrate that we’re not altering the rest of the cells, that our technology is completely inert,” says Cerf.

Figure 3. Representation of the CTC-Pheresis concept

Because SmartCatch is in silico — using computer modeling and simulation (CM&S) — Ansys products are helping them prove to regulatory authorities that their products do in fact work efficiently and are safe for human use. “Simulation is a very powerful argument to back up our experiments,” says Cerf. “We're not replacing physical experiments (in vitro) with simulated ones (in silico), but it's complementary information that in the end explains why we're making these choices.”