-

United States -

United Kingdom -

India -

France -

Deutschland -

Italia -

日本 -

대한민국 -

中国 -

台灣

-

Ansys stellt Studierenden auf dem Weg zum Erfolg die Simulationssoftware kostenlos zur Verfügung.

-

Ansys stellt Studierenden auf dem Weg zum Erfolg die Simulationssoftware kostenlos zur Verfügung.

-

Ansys stellt Studierenden auf dem Weg zum Erfolg die Simulationssoftware kostenlos zur Verfügung.

-

Kontakt -

Karriere -

Studierende und Akademiker*innen -

Für die Vereinigten Staaten und Kanada

+1 844,462 6797

ANSYS BLOG

October 10, 2019

What is Crosstalk? Electromagnetic Challenges and Trends

What is Crosstalk?

Crosstalk is the phenomenon where signals from one circuit or transmission line interfere with adjacent circuits or lines. Each signal generates varying electromagnetic (EM) fields. When these signals or circuits are situated close to each other, their EM fields overlap. This interference leads to an unwanted signal coupling causing crosstalk. Crosstalk can occur in electronic systems, such as printed circuit boards (PCBs), integrated circuits (ICs), and communication cables.

Engineers can no longer ignore electromagnetic crosstalk. They must understand what it is, how to find it and how to correct it.

The EM signals causing the interference are known as the aggressors, while the EM signal affected by crosstalk is known as the victim. Crosstalk occurs via two mechanisms:

- Capacitive crosstalk caused by the electrical field.

- Inductive crosstalk caused by the magnetic field.

Examples of Crosstalk

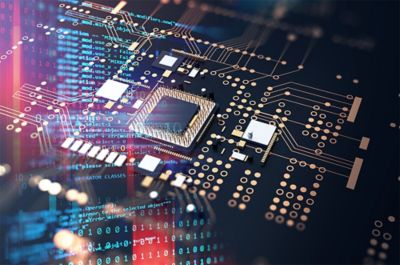

Printed Circuit Boards (PCB): PCBs involve complex circuit designs where multiple traces run close to one another. When a high-frequency signal passes through a trace, it induces a voltage in an adjacent trace due to capacitive or inductive coupling, causing crosstalk.

Integrated Circuits (ICs): Different components and interconnects are tightly packed in an integrated circuit. When an electromagnetic noise generated in one part of the IC (due to transistor switching) couples with the neighboring components, it causes crosstalk, which degrades its performance.

Communication Cables: In communication cables, such as ethernet cables, multiple twisted pairs transmit data. If the twists aren't tight enough or the cables are poorly shielded, signals from one twisted pair can crosstalk into adjacent pairs, leading to data corruption or reduced signal quality.

High-Speed Data Transmission: In high-speed data transmission, such as in HDMI or USB cables, signals can interfere with each other due to their high frequencies. This interference causes crosstalk and degrades the signal quality.

RF Systems: In radio frequency (RF) systems, crosstalk can occur between adjacent antennas or RF transmission lines. This can result in signal interference, reducing the effectiveness of the system.

Crosstalk in SOCs

Engineers developing system-on-chip (SoC) architectures that ignore crosstalk are taking a big risk. Crosstalk can produce electronic design errors that could lead to market delays and cost overruns.

The Challenges of Identifying EM Crosstalk

To help understand the complexities of EM crosstalk analysis, engineers can contrast the problem with capacitive coupling.

Capacitive coupling is strong in proximity and weaker at a distance. So, engineers can safely ignore capacitive coupling between signal lines that are far apart. In contrast, inductive magnetic coupling cannot be ignored between relatively distant signals.

It can be hard to determine if electromagnetic crosstalk is the source of an issue.

EM crosstalk is more challenging. First, the symptoms of the problem do not appear in one metric — like timing failure. Instead, crosstalk often manifests as a degradation in some key performance criterion that varies from design to design. Therefore, identifying the issue as crosstalk is the first challenge.

To make matters more complex, crosstalk usually involves unwanted coupling between digital, analog and radio frequency (RF) blocks. Either one can be the aggressor or victim.

EM crosstalk needs to be identified, debugged and resolved differently in different designs. Traditional solutions involve architecture or software tricks that prevent the modes of operation that trigger the problem. However, this is becoming financially and technically untenable as designs have grown in complexity and speed.

The Challenges of Modeling EM Crosstalk

To model EM crosstalk accurately, engineers need to analyze and model a staggeringly complex scope of physical structures, including:

- The nets of interest

- The surrounding structures that contribute to crosstalk

- Power and ground routing layers

- Bulk silicon substrates

- Package layers

- Bond/bump pads

- Routing layers

- Seal rings

- Metal fill

- Decoupling caps

Modeling EM crosstalk can be complex because of all the components that need to be included.

Most of these structures have complex physical layouts that require a large mesh to simulate the resistance, capacitance, inductance, coupling capacitance and mutual inductance.

A second modeling factor that increases the size of crosstalk models is that engineers can’t analyze EM crosstalk by limiting the focus to a small bounding box within the design. Analyzing neighborhood victim signals works well when assessing electrical capacitive coupling. However, magnetic fields can travel along large loops, form outside the immediate neighborhood of a victim signal or encircle the whole layout of the chip.

Additionally, it’s hard to limit the size of a model generated by EM crosstalk tools because it needs to include all the nets that contribute to the crosstalk problem and all the nets and structures that might have an impact on the performance of the circuit.

To be useful downstream in development, the crosstalk model must:

- Quickly compute in a simulation program with integrated circuit emphasis (SPICE)

- Operate in various nonlinear and noise simulations within a SPICE environment

- Exist in a database that crosses the boundaries of blocks or silicon dies

These three requirements are hard to meet given the typical size and complexity of crosstalk models.

The Emerging Need for EM Crosstalk Analysis in SoCs

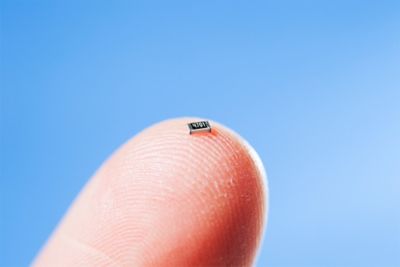

EM crosstalk is a big concern for engineers because of the demand for electronic systems to increase in bandwidth and decrease in size. This puts high-speed circuitry and high-bandwidth channels in proximity.

As electronics become smaller, crosstalk will become a bigger problem.

Additionally, the continuous increase in internal clock frequencies (5 to 10 GHz) and the increase in data rates (above 10 Gbps) are also fueling the emergence of crosstalk issues.

In short, fast speeds and small electronics create crosstalk; consumer demands are creating SoC trends that make it impossible to ignore parasitic inductance and inductive coupling.

SoC Architecture that Is Prone to Crosstalk

There are many architectural and application design trends that contribute to crosstalk.

For instance, EM crosstalk is frequency dependent. However, engineers cannot analyze EM crosstalk for a simple frequency of interest.

As an example, a clock signal with fast rise and fall times contains significant harmonic frequency components. So, a clock running at 10 GHz has a 5th harmonic frequency component running at 50 GHz.

Multiple ethernet lanes on the same system can become a crosstalk nightmare.

Those who target on-chip clock frequencies of 25 GHz, however, will have to think about how to safely model the 3rd harmonic, which falls into microwave frequencies.

EM crosstalk can affect signal magnitudes, or noise level. Hence, the impact of crosstalk is further exacerbated by the decrease in signal voltage levels and the increase in sensitivity to noise driven by lower-power trends in SoC applications.

Ethernet, fiber channel and peripheral component interconnects (PCI) can also be sources of crosstalk. To achieve high data rates, these buses employ multiple serial lanes that operate in parallel. For example, a 100 Gbps ethernet can employ 10 channels that are each running at 10 Gbps. When so many high-speed serial lanes reside in a single system, every lane can be a potential aggressor or a potential victim — a true crosstalk nightmare.

Other architectural trends that increase the likelihood of EM crosstalk include:

- High-speed analog blocks on one SoC

- Like phase-locked loops (PLLs) and voltage-controlled oscillator (VCO)

- Multiple high-speed clock networks on the same chip

- Clocks don’t need to operate at high frequencies — victim clocks running at 10 GHz can be affected by aggressor clocks running at 2 GHz.

- RF or high-speed analog blocks adjacent to high-speed digital blocks

- Shared ground nets and silicon substrates can’t be tapped as a ground.

- Silicon substrate remains a key noise-propagation channel between blocks.

- Seal rings and scribe lines inserted by foundries

- Low power designs with small signal-to-noise margins

- Sensitive control/reset signals that can be set by crosstalk glitches

- Integrated fan-out wafer-level packaging techniques

- Multiple dies in proximity increase the likelihood of EM crosstalk.

- Multiple dies in proximity increase the likelihood of EM crosstalk.

Crosstalk Solutions

SoC integration places high-speed digital circuitry, analog, and RF blocks close together and creates opportunities for crosstalk inside those components and across various blocks.

Most electronic design automation (EDA) tools are geared for a specific design type — such as digital, analog, or RF component design. However, crosstalk is not limited by these boundaries.

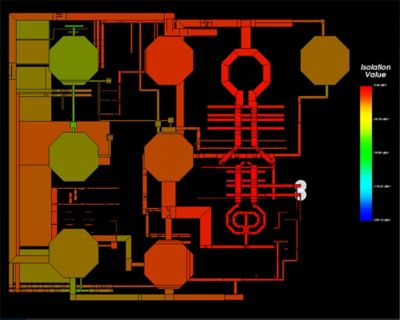

Ansys Pharos can help engineers identify crosstalk.

IC design engineers should be able to predict the coupling effects during the signoff phase. Using Ansys RaptorH IC, designers can accurately predict electromagnetic coupling effects and easily capture unknown crosstalk among different blocks in the design hierarchy.

To learn more about crosstalk, read the article: Optimize High-Speed Serial Links for Crosstalk.