-

United States -

United Kingdom -

India -

France -

Deutschland -

Italia -

日本 -

대한민국 -

中国 -

台灣

-

Ansys si impegna a fare in modo che gli studenti di oggi abbiano successo, fornendogli il software gratuito di simulazione ingegneristica.

-

Ansys si impegna a fare in modo che gli studenti di oggi abbiano successo, fornendogli il software gratuito di simulazione ingegneristica.

-

Ansys si impegna a fare in modo che gli studenti di oggi abbiano successo, fornendogli il software gratuito di simulazione ingegneristica.

-

Contattaci -

Opportunità di lavoro -

Studenti e Accademici -

Per Stati Uniti e Canada

+1 844.462.6797

ANSYS BLOG

August 31, 2022

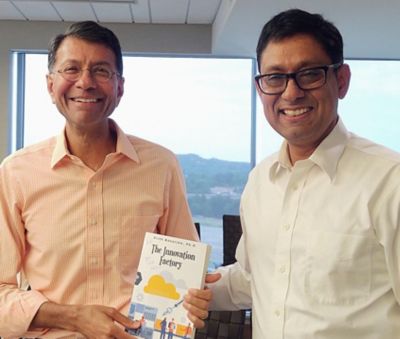

How to Turn Your Company Into an Innovation Factory

In his recently released book “The Innovation Factory,” Ansys CTO Prith Banerjee, Ph.D., distills his 35 years of experience in academia, startups, and large companies to present a vision of how to make innovation an ongoing process. Though other authors have made similar attempts, Banerjee’s book relies on his experience and that of other innovators he interviews to reveal “the ingredients of the secret sauce required to generate successful open innovation.”

Banerjee certainly has the credentials to speak on this matter. Before joining Ansys, he spent more than 20 years as a professor, chairman, and dean at the University of Illinois and Northwestern University. He founded two startup companies, AccelChip and Binachip. Finally, as the director of the iconic HP Labs and Accenture Labs, and as the CTO of ABB and Schneider Electric, he managed large research organizations.

The View From Three Horizons

The author borrows the concept of Three Innovation Horizons from the business book “The Alchemy of Growth: Practical Insights for Building the Enduring Enterprise” by Mehrdad Baghai, Stephen Coley, and David White of McKinsey & Company to frame his discussion:

Horizon 1 (H1): short-term innovation, mainly in the core product or service offered, e.g., sustaining, renewing, or in some cases reinventing the core offer.

"The Innovation Factory" book cover.

Horizon 2 (H2): medium-term innovation introduced in the core or adjacent offer, but driven at the business level.

Horizon 3 (H3): long-tail disruptive innovation, often introduced or driven by an outside influence, for example, acquiring a startup.

“Larger companies typically excel in Horizon 1 and also do a good job in Horizon 2 innovation,” Banerjee writes. “Universities typically focus on long-term Horizon 3 innovation; however, they often end their work at the discovery phase. Startup companies excel in taking Horizon 3 disruptive innovation to market. Large companies typically struggle with long-term Horizon 3 disruptive innovation.”

Accounting for the Differences Among Academia, Startups, and Established Companies

The reasons for these differences in performance lie in the rewards available to outstanding performers in each of these sectors. University professors are likely to be recognized for the number of papers they publish and the amount of funding they bring in, which can lead to fellowships and perhaps promotion within the university. Occasionally they will proceed to the startup stage, but not often; the comfort of tenure might outweigh the risks of a startup.

It’s more likely that graduate students at the beginning of their careers will take the risk of launching a startup that is laser-focused on a particular disruptive innovation they came upon in their graduate research. The risk is high but so are the potential financial rewards. And, being young, they can bounce back from a failure. Indeed, having failed at a startup is often a badge of honor and an incentive to venture capitalists to take a risk on experienced, though once-failed, entrepreneurs.

Established companies are more likely to be rewarded for steady improvement of their core line of products than taking a leap into the uncertainty of disruptive innovations. Businesses tend to be more conservative; publicly traded ones must listen to their stockholders. While the incremental approach may seem safer, they may be blind to new competitors with radically new products or processes that might leave them behind on the ash heap of once-profitable, now-failed companies.

All Together Now

The key to overcoming the various obstacles faced by established companies, startups, and academia is to combine all three into one open innovation initiative. This combination uses the strengths of one group to cover the weaknesses of the others. For instance, an established company might buy a startup to make up for its own weakness in the disruptive innovation department. Or a company might fund a university professor to pursue her ideas beyond the discovery phase in a particular research area of interest to the company. Banerjee calls this cooperative arrangement an “innovation factory.”

“The innovation factory is the practice and the implementation of H2 and H3 open innovation in which companies, whether large or small, partner outside their internal operations with universities, startups, and other business partners to develop innovative ideas and subsequently deliver them in the form of products and services to their customers,” he writes.

Ansys President and CEO Ajei Gopal (left) was presented with a copy of "The Innovation Factory" by Ansys CTO Prith Banerjee (right).

The Role of a Central Research Lab in Innovation

Experts often suggest that the key to established companies creating disruptive innovation is to form a central research lab (CRL), such as Bell Labs, IBM Research, Microsoft Research, HP Labs, Xerox PARC, and General Electric Research. These highly successful labs have produced many of the greatest innovations of the last century.

But sometimes CRLs fail because they are disconnected from the central business entity, with its sales and marketing arms. They innovate greatly but have no way to sell their innovations. The main sales team for the company may be great at selling their core products but have difficulty in understanding and selling disruptive products.

“If you are going to create a central research lab, you must give that CRL a small sales team to sell what they're building," Banerjee said in an interview about the book. “So, that's concept number one — it’s called incubation. You should have a CRL with an incubation arm, so they're doing the whole thing from R&D to sales and marketing of that particular product.

“Concept number two is that all the smart people will not work in the CRL. There are a whole bunch of smart people outside in academia and startups and so on, and the role of the CRL should be to scan what's out there in the world and bring the best innovations back to the team.”

For instance, after determining that a startup’s software could be made to interact with Ansys software and improve its functionality, an OEM agreement could be set up to sell the product on the Ansys price list. If it sells, Ansys might buy the startup and incorporate their innovative thinking into the Ansys family.

“Open innovation is a very well-defined process,” Banerjee concluded in the interview. “Let's scan the world. What's out there?”

To learn more, get your copy of "The Innovation Factory" on Amazon.