-

United States -

United Kingdom -

India -

France -

Deutschland -

Italia -

日本 -

대한민국 -

中国 -

台灣

-

Ansys s'engage à préparer les étudiants d'aujourd'hui à la réussite, en leur fournissant gratuitement un logiciel de simulation.

-

Ansys s'engage à préparer les étudiants d'aujourd'hui à la réussite, en leur fournissant gratuitement un logiciel de simulation.

-

Ansys s'engage à préparer les étudiants d'aujourd'hui à la réussite, en leur fournissant gratuitement un logiciel de simulation.

-

Contactez-nous -

Carrières -

Étudiants et universitaires -

-

S'inscrire -

Déconnexion -

Espace client -

Support -

Communautés partenaires -

Contacter le service commercial

Pour les États-Unis et le Canada

+1 844.462.6797

-

ANSYS BLOG

December 03, 2019

The Complete Guide to Designing Aircraft Lights

When asked to list key airplane components, a frequent flyer might not think about aircraft lights. The engines, wings and landing gear all spring to mind due to their strong association to operations and safety.

Engineers know better. A rivet or brace could mean the difference between a safe or disastrous flight.

Engineers know how challenging it is to create aircraft lights that meet expectations.

Airplane lights are no different. They show up on a plane’s exterior, cockpit and cabin. Each fixture has a purpose, function and setup. Engineers are challenged to incorporate them into various configurations, so they don’t interfere with comfort, utility or safety.

To reduce physical testing, engineers are turning to optical simulations to design illumination systems that meet airline, passenger and regulator expectations.

How to Design Exterior Aircraft Lights

It can be time consuming to design, test and validate an airplane’s exterior lighting system, which helps pilots navigate, avoid collisions, land, taxi and signal other aircraft. As a result, their functional safety is a top priority.

These systems are often tested and validated using physical prototypes. Sometimes, engineers need to test the equipment under conditions that are hard to schedule or predict.

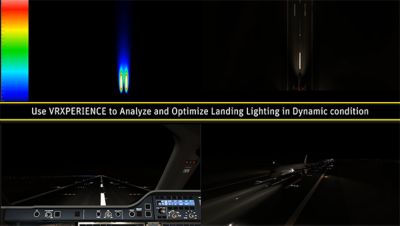

Engineers can use simulation tools, like Ansys VRXPERIENCE, to analyze and optimize aircraft landing lights.

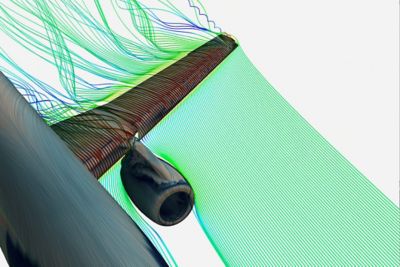

Simulation can help to eliminate much of the physical testing needed to validate the exterior aircraft’s lights. Photometry, colorimetry, homogeneity and overall performance can be tested in various configurations, weather conditions and operations — like landing, takeoff or taxiing.

As a result, engineers don’t have to wait for the perfect storm to test their designs. They can test them digitally while reducing budgets and time to market. The engineer can even set up a simulation to run multiple times, to better optimize a design for edge cases that are impossible to test using physical prototypes.

How to Design Airplane Lights in the Cabin

The lights in a cabin have various uses. They can provide comfort, safety, utility and uniform illumination. The challenge engineers face is that the function of one fixture could interfere with the function of another.

The airplane lights within the cabin need to offer passengers comfort, functionality and safety.

A typical airline feature is to set an ambient mood that comforts passengers. These moods also help passengers climatize to their destinations by mimicking sunrise, daytime, evenings and nighttime.

The ambient mood, however, can be affected by fixtures that provide practical utility. The ceiling and sidewall fixtures may not be much of a problem but the spotlights that help passengers read could affect the nighttime ambiance of those around them.

Though it is important to make sure mood and practical fixtures work together in a cohesive experience, they take a back seat to emergency lighting systems. In this case, engineers are challenged to create systems that blend into their surroundings (to avoid triggering anxieties during normal flights) while clearly pointing people toward exits and emergency equipment during crises.

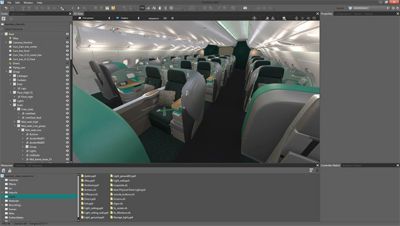

Engineers can use simulation to optimize the comfort, practicality and safety of cabin illuminating systems. They can do this by altering parameters like a system’s color, intensity and source as well as the materials being illuminated — like carpets or seat leather.

How to Optimize Cockpit Lighting in Aircraft

The lighting systems in a cockpit are similar to those in the cabin, in so far as they need to offer pilots comfort, utility and safety. The difference is that these systems need to optimize how pilots perform.

Engineers need to design cockpits with lighting systems that optimize the pilot’s performance in any situation.

For instance, the cockpit will be lit and colored in a way to preserve vision in dark or dazzling situations. The lumens produced by instrumentation are optimized to help pilots see important data without obscuring other equipment. Engineers also need to test all these systems in various conditions to prevent glare, reflections and eyestrain.

However, these assessments are often done late in the development cycle. As a result, fixes could become costly and time-consuming. By testing the illumination of the cockpit using simulation, engineers can analyze it at an earlier stage of development.

These simulations could then inform the design of the human machine interface (HMI) between the pilot and the aircraft. This enables engineers to quickly optimize instrument panels, obstructions, glare and reflections in various flight and lighting conditions.

Simulation Tools for Aircraft Lighting Design

Ansys VRXPERIENCE and Ansys Speos can run the simulations that engineers need to optimize an aircraft’s exterior, cabin or cockpit lighting.

Engineers can use Ansys VRXPERIENCE and Ansys Speos to test aircraft lights in various configurations and conditions.

In fact, these simulations can be coupled with a human eye model to assess the illumination, glare and reflections from a physiological point of view. Engineers can even design virtual realities where they can experience these environments for themselves — before any physical prototypes have been made.

The software also enables engineers to cycle through various setups, fixtures, materials, weather and environmental situations to ensure systems run properly — and avoid interfering with each other — during landing, takeoff, taxiing, cruising or emergency situations.

To learn more, view the on-demand webinar: Making the Cockpit of the Future a (Virtual) Reality.