-

United States -

United Kingdom -

India -

France -

Deutschland -

Italia -

日本 -

대한민국 -

中国 -

台灣

-

Ansys is committed to setting today's students up for success, by providing free simulation engineering software to students.

-

Ansys is committed to setting today's students up for success, by providing free simulation engineering software to students.

-

Ansys is committed to setting today's students up for success, by providing free simulation engineering software to students.

-

Contact Us -

Careers -

Students and Academic -

For United States and Canada

+1 844.462.6797

ANSYS BLOG

January 17, 2023

Centering Human Vision in Vehicle Display Design

Engineering excellence doesn’t exist without empathy for the end user. You can design a structurally robust steering wheel, but if it’s in the wrong position, it doesn’t serve its main purpose — to be steered. Likewise, when designing for human vision, a display doesn’t need the highest possible luminosity or energy output. An optical engineer might be looking for these qualities, but that expectation overlooks the purpose of the design. Optimizing a vehicle display is about centering the end user and the way they perceive the world around them.

When it comes to functionality, there are a number of design areas that offer opportunities for improvement:

- Character size: Designing displays to reduce pixel size accommodates low resolution, so fine images can be displayed on the screen.

- Contrast: Legibility is impacted by perceived contrast between text and background. In low-contrast conditions, typography is more difficult to see — especially in a navigating scenario where the driver’s focus should be on the road.

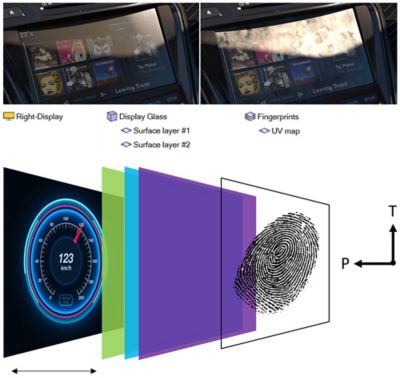

- Texture: When a display is covered in dirt or oily fingerprints, it’s more difficult to read under critical sun positions (Figure 1). Dust on a camera or raindrops on a windshield create similar issues to contend with.

- Machine-human interaction: The physical position and orientation of the display impacts how the driver and passengers perceive the screen. Optimization improves the general quality of human-machine interaction.

- Field of view: More relevant for heads-up displays (HUD), engineers are designing optical technologies that support a larger field of view and can layer projected information on top of real-world conditions. These technologies are expected to fit in small spaces to avoid disrupting the dashboard aesthetic or taking up precious volume under it.

Designing for Human Perception in Practice

Early on, engineers work to design a display on the nanoscale by testing how light interacts with different geometries like LED crystals or OLED layers. As the design scales up from photonic component modeling to optical component modeling, the focus shifts to elements like polarizing layers and surface coatings. As most automakers rely on outside vendors for display technology, the final stages of design are focused on integrating the display into the vehicle.

Sun studies identify critical sun positions and account for reflections from other light sources. In some cases, post-processing algorithms allow users to see screen effects like glare. Ansys’ algorithm accounts for the biology of the human eye with features that emulate adaptation time or even color blindness. If the driver is in the dark for five minutes and their eyes suddenly hit the display, they’re going to perceive it differently than they would after five minutes in bright light. The eye is constantly adapting to light settings, and the right simulation tools can render these kinds of realities.

Figure 1: Human perception of display with fingerprints versus a clean display at a critical sun position.

When simulating human vision using physics-based rendering, predicting the quality and performance of a future product is more valuable than creating a realistic render of an existing prototype. One of the key requirements for physics-based renderings is high-performance computing (HPC) on central processing units (CPUs) or graphics processing units (GPUs). Ansys is quickly adding GPU support because they operate closer to real time. These results can be analyzed and experienced, using the human eye parameters mentioned above, in the Ansys Human Vision Lab.

At the end of the day, specifications are important, but sometimes they come from uninformed sources or are simply stricter than the application demands. Simulation software can get results fast, but there’s something to be said for experiencing the end product. When a driver gets into a vehicle, they won’t be measuring how much light comes out of the display, but they will be thinking about the way that vehicle makes them feel. The ability to anticipate those feelings and perceptions — and make design decisions without over-engineering — makes virtual prototyping an incredibly valuable tool.

Don’t just look at the numbers — experience your results. For more information on luminance matching and human vision, watch our on-demand webinar.