-

United States -

United Kingdom -

India -

France -

Deutschland -

Italia -

日本 -

대한민국 -

中国 -

台灣

-

Ansys is committed to setting today's students up for success, by providing free simulation engineering software to students.

-

Ansys is committed to setting today's students up for success, by providing free simulation engineering software to students.

-

Ansys is committed to setting today's students up for success, by providing free simulation engineering software to students.

-

Contact Us -

Careers -

Students and Academic -

For United States and Canada

+1 844.462.6797

ANSYS BLOG

April 24, 2024

Discussing In Silico Medicine in Congress and Parliaments

Billions of people around the world are waiting for a new pharmaceutical drug or medical device to improve their quality of life — or maybe even to save them. Unfortunately, some will die waiting, and it doesn’t have to be this way.

A technology shift to an in silico clinical trial (ISCT) approach — which uses virtual human patients based on a blend of realistic anatomical data, physiological information, and computational modeling and simulation (CM&S) techniques — can supplement (or even replace) human participants in traditional clinical trials. This would greatly reduce the time and cost to develop new drugs and obtain regulatory approvals. But this would require the acceptance of simulated clinical results by global health authorities. So far, only the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has formally taken this step.

Ansys has been instrumental in promoting the ISCT approach to U.S. Congress members and to parliament members in the European Union (EU) and other regions of the world. For more than a decade, Ansys employees Marc Horner and Thierry Marchal have shared their perspectives and insights regarding ISCT to the healthcare community, including regulators, policy makers, and standards organizations. With the help of their in silico colleagues from industry and academia, they are successfully converting the equations of engineering simulation into new legislation and standards.

Thierry Marchal (third from left) at the European Parliament

Starting by Joining Forces

The Avicenna Alliance, founded in part by Ansys, is devoting time and effort to convince politicians, policymakers, and regulatory agencies around the world that ISCTs are the future. Founded in 2016 at the suggestion of the European Commission, the Avicenna Alliance advocates for the regulation and deployment of in silico medicine. It comprises leading pharmaceutical and medical device companies — both established market leaders and startup companies — and has partnerships with many regulatory and standards agencies. Additionally, 50% of its members are from academia, ensuring that the advances of basic research are both well represented and implemented.

“By joining together in the Avicenna Alliance, we are not speaking in the name of Ansys or any other single company,” says Thierry Marchal, Secretary General of the Avicenna Alliance for the past eight years and Program Director of Healthcare Solutions at Ansys. “We are speaking in the name of all these organizations who are willing to accelerate care to the patient. So this is changing things completely in that people are willing to listen.”

Marchal, who has spoken about ISCTs to the European Commission, members of the U.S. Congress, the Brazilian Parliament, United Kingdom leaders, regulators in Australia, and many other government organizations worldwide, is quick to point out that Alliance members are there not only to talk but also to listen.

“We are not there to tell them ‘Here is what you need to do,’” he says. “All these organizations have the same motivation as us — bringing the latest and most advanced therapies to the patient as quickly and safely as possible. We tell them that there is a very good technology — in silico technology — that is accepted by the FDA, and you should learn about it. And we are asking the question, ‘What do you need in order to be convinced that this is valuable?’”

Beyond high-level parliamentary discussions, Ansys is also involved in pushing ISCTs forward on the regulatory side. Marc Horner, Distinguished Engineer at Ansys and Vice Chair of the ASME VVUQ (verification, validation, and uncertainty quantification) 40 sub-committee, works to develop standards that support VVUQ for medical device industry applications. One output of this sub-committee is the ASME V&V 40 standard, which defines a risk-based framework for establishing model credibility. This standard was used as the basis for the Medical Device Innovation Consortium’s Virtual Patient project, where Marc was part of a team that demonstrated how an ISCT could be used as part of a regulatory submissions to the FDA.

In spite of these successes, one roadblock is that ASME standards are not formally recognized globally, therefore other countries are understandably hesitant to adopt them. To address this, “ASME, Avicenna, and others are currently seeking approval to develop an IEC standard that recognizes ASME V&V 40,” Horner says. “The new standard would recognize that there is a continuum of models, ranging from knowledge-based to data-based, which all require credibility assessment. This standard would hopefully address the issue of global acceptance without re-inventing the wheel.”

How ISCT Can Overcome the Challenges of Clinical Trials

Marc Horner joining colleagues from Edwards Lifesciences and VPHi at ANVISA, the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency

Unlike consumer products, medical solutions require regulatory approval before they can be released to the public to ensure they are safe and effective, and this takes a lot of time. For example, regulatory approval of a novel medical device takes between five and six years and typically costs up to $100 million. For a new pharmaceutical, these numbers can be 10 to 15 years and 2.5 billion dollars.

The long lead times and high expenses are mostly due to multiple levels of clinical trials required for approval. Initial lab testing (aka in vitro, in glass) testing using no living subjects is followed by a round of testing on laboratory animals (in vivo, involving living creatures), and finally, human trials. Finding 5,000 to 10,000 people who agree to participate in human trials is a challenge in and of itself. And if the medical solution is designed to address a rare disease, then getting significant numbers of participants to yield statistically relevant results is even more difficult.

ISCTs can help in a number of ways.

The most obvious is by creating simulated human models to add to the clinical testing pool. If you need people with conditions x, y, and z in your testing pool, but do not have any human volunteers with these conditions, you can create virtual humans that reflect these requirements. In addition, in silico technology can be used to:

- Reduce the overall number of participants or trial duration

- Refine the trial to minimize suffering or improve its relevance to humans

- Replace (completely) the trial with in silico testing

“We can test hundreds, thousands, and even millions of virtual patients relatively quickly using in silico methods,” Marchal says. “It’s just a question of computational time and energy.”

Thierry Marchal (third from left) in front of the United States Capitol

Developing A Common Language to Promote Trust

Marchal and Horner, together with their in silico partners, have been traveling the world in recent years to talk to lawyers, politicians, policymakers, and regulators to convince them that ISCTs are the correct path forward. They are also meeting with other important stakeholders within medical device and drug companies, such as research and development leaders, quality assurance, and regulatory affairs professionals who can advocate for in silico approaches internally at their organizations.

“We need to talk to all the people,” Marchal says. “None of them are opposed to what we are proposing. But before making a decision, before changing the law or transforming development processes, they need to be convinced that what we are proposing is a good thing.”

Marchal and Horner believe that it’s only natural that they should have questions, because what they are proposing is not intuitive.

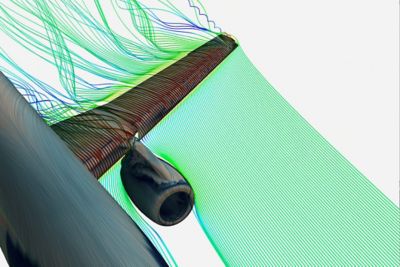

“The key argument is that we can replace clinical testing of humans with computer models,” Marchal says. “Really? Are the computer models good enough? Are the colorful pictures we are showing of fluid flow in the heart and the lungs accurate and valuable? Are they fully validated? And can you define what ‘validated’ means?”

These are just some of the questions that Marchal and Horner have been answering in their ISCT efforts. The fact that the questions are coming from people of varying backgrounds increases the challenge.

“We’ve got the same goals, but we need to learn to speak each other’s language,” Horner says. “We believe that it is up to us to learn to speak the language of the regulator, the politician, and even the clinician in some cases, and they are doing their best to understand our language. If you are speaking to someone who is not an engineer, you’re not going to convince them by showing them convergence plots from simulations. The results have to be translated into a language or outcome that is meaningful to them.”

Even in places where decision makers are convinced of the necessity of using in silico methods, sometimes it is difficult to find anyone besides the regulatory authority who has the knowledge to review this kind of computer model.

“This means we have to provide training, to inform the non-expert about in silico, and we have to go beyond the modeling to provide information about regulatory best practices,” Horner says.

The Race Is On

Many global medical device and pharmaceutical companies are already using engineering simulation to develop new products, but few are invested in using simulations for regulatory approval, mainly because the regulators in their countries have not yet provided a formal framework for the acceptance of in silico data.

Developing an international (ISO or IEC) standard would go a long way in overcoming this barrier, and that is what the Avicenna Alliance is now pushing for. Meanwhile, patients in countries that have longer regulatory approval processes might suffer.

“I’m trying to convey this feeling to the different authorities that we are in a race,” Marchal says. “The only winners of this race will be the patients. If you do not allow a new medical product to be validated with the in silico method, it could take a long time to get validated and approved, and during this time your local citizens cannot access this technology while the same technology might be saving lives in the U.S., but not yet in Europe. This is kind of a punishment for the local citizen.”

To advance these efforts, the European Parliament recently voted to amend its General Pharmaceutical legislation stating that, "Data generated via in silico methods, such as computational modelling and simulation, molecular modelling, mechanistic modelling, digital twin and artificial intelligence, where appropriate, could also be used to support regulatory decision making."

Through the Avicenna Alliance, governments, politicians, clinicians, engineers, academicians, and software providers are working as a community to ensure that every country and every citizen will be winners in this race. If we can adopt international regulatory standards for faster approval of medical procedures, treatments, and devices using simulated clinical trial results, we can save lives worldwide instead of just in small areas of the globe. If you are not already involved in this effort, we encourage you to join us today.